Paper list

1. DianNao: A Small-Footprint High-Throughput Accelerator for Ubiquitous Machine-Learning [ASPLOS’14]

2. SCALE-Sim: Systolic CNN Accelerator Simulator [arXiv’18]

3. Eyeriss: A Spatial Architecture for Energy-Efficient Dataflow for Convolutional Neural Networks [ISCA’16]

4. Cnvlutin: Ineffectual-Neuron-Free Deep Neural Network Computing [ISCA’16]

5. Cambricon-X: An Accelerator for Sparse Neural Networks [MICRO’16]

6. SCNN: An Accelerator for Compressed-sparse Convolutional Neural Networks [ISCA’17]

7. EIE: Efficient Inference Engine on Compressed Deep Neural Network [ISCA’16]

8. ESE: Efficient Speech Recognition Engine with Sparse LSTM on FPGA [FPGA’17]

9. Scalable Multi-FPGA Acceleration for Large RNNs with Full Parallelism Levels [DAC’20]

10. MnnFast: A Fast and Scalable System Architecture for Memory-Augmented Neural Networks [ISCA’19]

11. Manna: An Accelerator for Memory-Augmented Neural Networks [MICRO’19]

diannao

1. DianNao: A Small-Footprint High-Throughput Accelerator for Ubiquitous Machine-Learning [ASPLOS’14]

Motivation

Layers of state-of-art CNNs consist of thousands of neurons and millions of synapses.

During processing the large networks, general purpose hardware (e.g., SIMD processors, and GPUs), and previous accelerators have shown memory inefficiency.

They not only confirm the observation that dedicated storage is key for achieving good performance and power but also try to improve locality at the level of registers located close to computational operators with tiling that can reduce the data movements.

Methodology

They first describe tiling methods of three CNN layers: convolutional, pooling, and classifier (fully-connected).

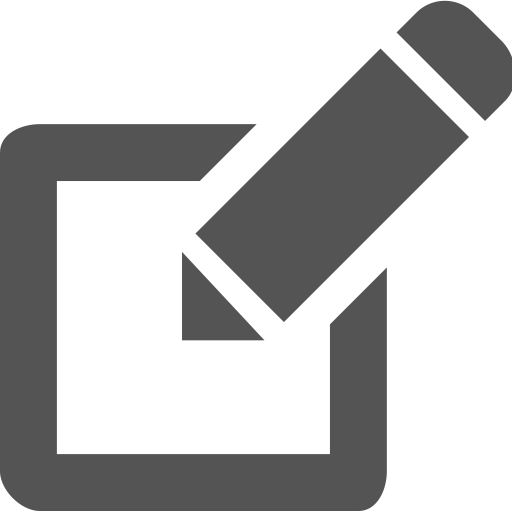

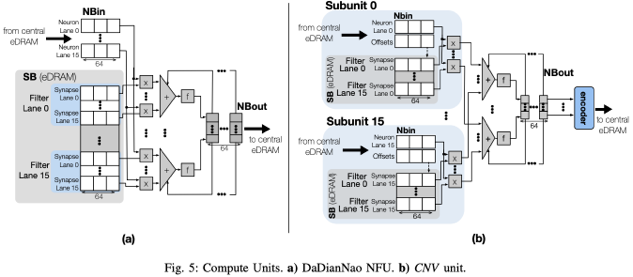

To implement large neural networks, they propose an accelerator, called DianNao in Figure 11. The accelerator is composed of input neuron buffer (NBin), synaptic weight buffer (SB), output neuron buffer (NBout), and neural functional unit (NFU).

The three buffers are separated and constructed as scratchpads.

NFU is divided into three stages: multiplication, adder tree, and sigmoid.

For the implementation of a single layer on the accelerator, a tiling factor called Tn is used for the accelerator design.

Differences from prior work

The previous studies have focused on efficiently implementing the computation part of neural network algorithms. However, they tend to ignore data movements, which are costly during inference, and thus this work considers reducing the data movements.

Pros & cons

[Pros] To reduce memory latency, they use DMAs (two load DMAs, and one store DMA) that can preload data during NFU operations, and the DMAs allow the accelerator to exploit spatial locality. For temporal reuse of input neurons, the NBin buffer is rotated with register index implementation (software). They also consider partial sums feedback (between NBout buffer and NFU-2 stage) to avoid conflicting memory access for output neurons. [Cons] Since DianNao cannot exploit weight reuse, it can be inefficient to process layers that have large amounts of weights. In addition, due to the adder tree structure, the accelerator is less scalable. Lastly, fixed tiling factor (Tn) may lead to underutilization of each buffer according to layers.

scale-sim

2. SCALE-Sim: Systolic CNN Accelerator Simulator [arXiv’18] [github]

Advanced Version: A Systematic Methodology for Characterizing Scalability of DNN Accelerators using SCALE-Sim [ISPASS’20]

Motivation

The authors mention that there was no cycle-accurate DNN accelerator before SCALE-Sim. The lack of accelerator analysis tools is the main motivation of this paper. It provides systolic array based accelerator analysis by taking various microarchitectural features. This tool allows architects to know principled insights on both the design trade-offs and efficient mapping strategies for accelerators. However, since this paper is not a conference paper, motivation and contribution to this paper are weaker than other papers. Thus, the authors have developed this paper’s methodologies to publish to a conference, and the advanced version of this paper was finally published in ISPASS’20. The advanced version focuses on scalability of accelerators that is described as scaling-up and scaling-out in the original.

Methodology

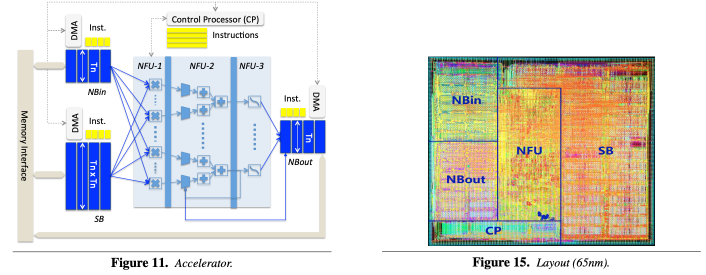

SCALE-Sim takes several parameters, such as array size, scratchpad memory size, dataflow strategy, and DNN layer parameters, and then reports latency, array utilization, memory accesses, and DRAM bandwidth requirement. In the paper, they provide a method of DNN layer mapping on a systolic array based accelerator depending on three dataflow: input-stationary (IS), weight-stationary (WS), and output-stationary (OS).

Differences from prior work

Since SCALE-Sim is the first public and open source CNN accelerator simulator, it is hard to explain the comparison between this paper and prior work.

Pros & cons

[Pros] Using SCALE-Sim, architects can consider the design of scalable DNN accelerators. [Cons] However, since only systolic array based accelerators are available with this tool, architects have to use other tools or methodologies to design accelerators of different structures, such as adder tree based accelerators, and 3-level accelerators.

eyeriss

3. Eyeriss: A Spatial Architecture for Energy-Efficient Dataflow for Convolutional Neural Networks [ISCA’16]

Cross-referenced paper: An Energy-Efficient Reconfigurable Accelerator for Deep Convolutional Neural Networks [JSSC’16]

Motivation

Highly-parallel computing hardware, such as SIMD/SIMT machines, can achieve high throughput during DNN processing. However, the DNN computational complexity, which comes from high-dimensional DNN layers, can make the machines energy inefficient from a large amount of data movement. Hence, finding a proper dataflow that brings about the minimal data movement cost is crucial to achieving energy efficient DNN processing. In this paper, they categorize existing dataflows (e.g., IS, WS, OS, and NLR) and propose their own dataflow called row-stationary (RS). They also introduce a fabricated chip, called Eyeriss, which uses the RS dataflow.

Methodology

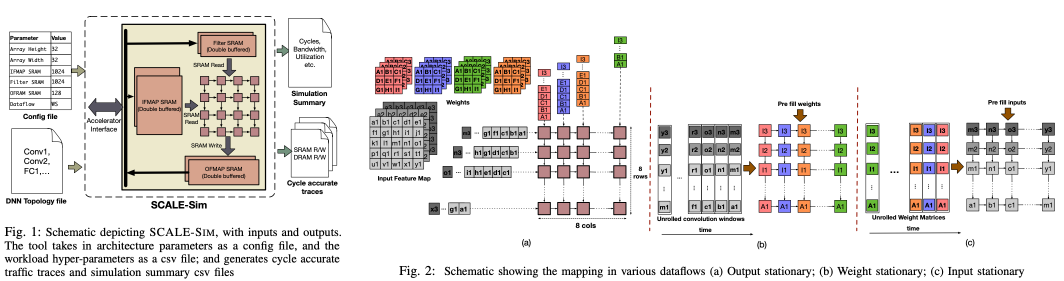

Eyeriss consists of three levels: global buffer, register files (RFs), and multiply-and-accumulate (MAC) units. The chip employs 108KB shared memory, where 100KB of space is assigned to input and output data, and the rest is used for filters in FIFO fashion. In each PE, there are separate buffers for input, filter, and output data totaling 0.5KB. PE array, which is made up of 168 (14 x 12) PEs, creates RS dataflow by mapping input height and filter height to PE array X and Y. Due to this mapping, the row-direction data (e.g., input rows, filter rows, and output rows) are moved between adjacent levels, and thus they call the data row primitives.

Differences from prior work

They establish a novel dataflow called RS, and the dataflow is more energy efficient than existing dataflows in both convolutional and fully-connected layers.

Pros & cons

[Pros] Eyeriss outperforms prior accelerators by 1.3x to 2.5x in energy efficiency, because of the reduced data movement between adjacent memories. [Cons] Since the chip is reconfigurable, layer-by-layer compilation (or mapping) is required for efficient DNN layer scheduling, and the process is quite difficult and time-consuming.

cnvlutin

4. Cnvlutin: Ineffectual-Neuron-Free Deep Neural Network Computing [ISCA’16]

Motivation

A large fraction of the computations performed by DNNs are intrinsically ineffectual as they involve a multiplication where one of the inputs is zero. The ineffectual computations can be skipped by taking additional units and control flow. The value-based DNN acceleration approach can enhance power efficiency and reduce execution time, and thus it can improve overall EDP and ED^2P.

Methodology

Cnvlutin (CNV) unit is based on DaDianNao which consists of neuron lanes (NBin) and filter lanes (SB), and adder trees. The neuron lanes of baseline are distributed to corresponding subunits in CNV. A filter lane is composed of multiple synapse sublanes, and the sublanes are also distributed to corresponding subunits in CNV. To skip ineffectual computations from input zeros, CNV has offset buffers for each subunit. The offsets adjust the synapse sublane’s index, so that it can access the appropriate synapse column. After MAC operations, output neurons are encoded for the next layer. The CNV encoder rearranges output neurons and creates output neuron offsets.

Differences from prior work

Prior works targeted at accelerating sparse vector matrix operations using FPGAs, GPUs, or other many-core architectures. However, CNV is designed for the specific access and computation structure of convolutional layers of DNNs. Compared to a DNN accelerator, Eyeriss is a low power, realtime DNN accelerator that exploits zero valued neurons by using run length coding for memory compression. Eyeriss gates zero neuron computations to save power but it does not skip them as CNV does (i.e., Eyeriss cannot reduce execution time).

Pros & cons

[Pros] If the sparsity of a DNN layer is high, CNV can achieve power efficiency and execution time reduction. [Cons] However, since the sparsity is not unpredictable, corner cases may exist (e.g., non-zero input case).

cambricon-x

5. Cambricon-X: An Accelerator for Sparse Neural Networks [MICRO’16]

Motivation

Although the number of operations and memory accesses can be greatly reduced with synapse pruning that brings about sparse and irregular neural networks, general purpose hardware and existing accelerators have not been able to exploit the pruning technique. To maximize efficiency, Cambricon-X utilizes the sparsity and irregularity of neural networks by taking an indexing module (IM). IM efficiently selects and transfers needed neurons to connected PEs with reduced bandwidth requirement, while each PE stores irregular and compressed synapses for local computation in an asynchronous fashion.

Methodology

Cambricon-X is based on DianNao, and thus each PE in Fig. 4 has an adder tree they call a PEFU. The difference between two architectures is the existence of a buffer controller (BC) which can exploit the sparse and irregular features. The BC is designed for transferring necessary neurons to PEs, orchestrating computations on PEs, and performing less computation-intensive operations. The controller consists of an indexing module (IM), and a specialized function unit for the BC (BCFU). To implement the IM, they introduce two commonly-used indexing options: direct indexing and step indexing. Step indexing is more efficient in terms of area and power than direct indexing.

Differences from prior work

Prior accelerators (e.g., DianNao and DaDianNao) fill the pruned synapses with zero values, incurring significant waste of computational resources. In addition, the accelerators cannot adapt to the irregularity of sparse neural networks. However, Cambricon-X can ignore the zero weight synapses to reduce energy consumption and execution time.

Pros & cons

[Pros] Since the total number of operations is reduced by the neuron indexing method, Cambricon-X achieves speedup and energy saving. [Cons] However, the architecture cannot exploit the sparsity opportunity of input activation.

scnn

6. SCNN: An Accelerator for Compressed-sparse Convolutional Neural Networks [ISCA’17]

Motivation

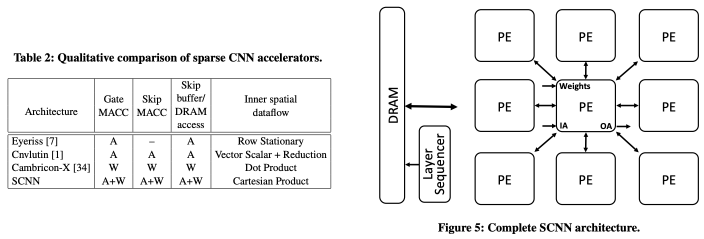

Sparse neural networks have emerged as an effective solution to reduce the amount of computation and memory required. The opportunities of the efficient reduction come from the zero-valued weights and zero-valued activations. The former data stem from network pruning during training, and the latter data arise from the common ReLU operator. To exploit the zero values, previous accelerators have been leveraged only for single-type data. Table 2 shows how the accelerators and SCNN (this work) exploit sparsity. Eyeriss exploits sparsity in activations by storing them in compressed form in DRAM and by gating computation cycles for zero-valued activations to save energy. Cnvlutin moves and stages sparse activations in compressed form and skips computation cycles for zero-valued activations to improve both performance and energy efficiency. Conversely, Cambricon-X exploits sparsity by compressing the pruned weights, skipping computation cycles for zero-valued weights, but it still suffers from wasted computation cycles when the non-zero weight is to be multiplied with zero-valued activations. Compared to the three accelerators, SCNN leverages all of the sparsity opportunities.

Methodology

They propose PT-IS-CP-sparse dataflow. The word order in the dataflow notation (i.e., PT -> IS -> CP) means the order of process in the SCNN accelerator. If the number of output activations (W x H) for each channel (K) is larger than the number of PEs, the activations are partitioned into planar tiles (PTs), and the tiles are handled by the PEs in the same cycle. The PEs hold input data temporally for input-stationary (IS), weight neurons are broadcast to the PEs. In each PE, an array of F x I multipliers computes a full cartesian product (CP) of output partial sums using non-zero values (sparse value skipping). Each multiplier output is accumulated with a partial sum at the matching output coordinates in the output activation space.

Pros & cons

[Pros] SCNN can leverage all of the sparsity opportunities including input activations and weight neurons. [Cons] The assumption that the size of an input activation plane and the size of an output activation plane are the same as W x H creates additional input zero paddings. Although SCNN skips all the zero values, the additional zero values can raise coordinate computational overhead or compression overhead.

eie

7. EIE: Efficient Inference Engine on Compressed Deep Neural Network [ISCA’16]

Motivation

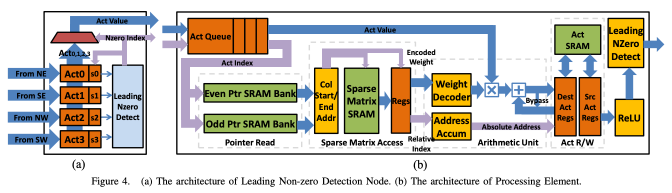

During matrix multiplication, the memory access is usually the bottleneck especially when the matrix is larger than the on-chip buffer capacity. Also, there is no reuse of the weight matrix, and thus a memory access is required for every operation. Therefore, an efficient way to execute a large matrix multiplication layer (e.g., FC layer) is needed. Network compression via pruning and weight sharing makes it possible to fit the layers. However, processing these compressed layers is challenging. To efficiently operate on the compressed layers, they propose EIE, an efficient inference engine, a specialized accelerator that performs customized sparse matrix vector multiplication and handles weight sharing with no loss of efficiency.

Methodology

To exploit the sparsity of activations, an encoded sparse weight matrix is stored in a variation of compressed sparse column (CSC) format. The variant format consists of virtual weights, relative row indices, and column pointers. EIE has multiple PEs, and non-zero Input activations are distributed to each PE. In Figure 4(a), the non-zero activations are detected by the leading non-zero detection (LNZD) nodes. Each LNZD node finds the next non-zero activation across its four children and sends this result up the quadtree. A central control unit (CCU) receives the non-zero activations and broadcasts these to the PEs. Figure 4(b) illustrates the architecture of a PE in EIE. Two column pointers are read from a pointer read unit in one cycle. A sparse matrix access unit uses the two pointers to read the non-zero weight neurons. The arithmetic unit receives a weight index and a relative row index, and performs MAC operation. To sum up, the sparse activation operations are eliminated by LNZD, and the sparse weight neurons are automatically ignored by the compressed format.

Differences from prior work

Compressed layers are not efficient on previous sparse matrix multiplication (SPMV) accelerators. The accelerators can only exploit the static weight sparsity except for the dynamic activation sparsity. On the other hands, EIE exploits both, and additionally supports weight sharing.

Pros & cons

[Pros] Due to the weight compression, EIE achieves high throughput and energy efficiency. [Cons] EIE can have a worse performance in batch operation than hardware to support the operation. The accelerator should be developed to handle convolutional layers.

ese

8. ESE: Efficient Speech Recognition Engine with Sparse LSTM on FPGA [FPGA’17]

Motivation

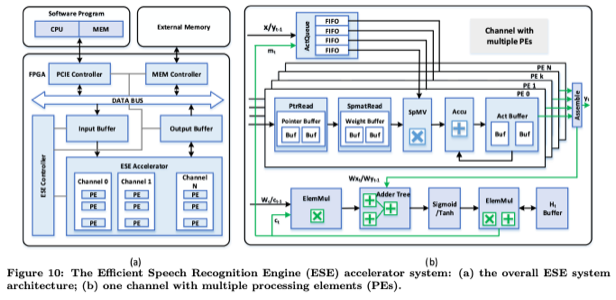

In the speech recognition process, LSTM networks are used for an acoustic model, and these are the most computation and memory intensive parts. To achieve higher prediction accuracy, large networks are used. As the networks grow, the opportunity to exploit the sparsity also increases. Although pruning and quantization can reduce memory footprint, some new challenges arise: 1) irregular computation, 2) load imbalance, and 3) failure to use the parallelism of compressed LSTM. General purpose processors cannot implement these challenges efficiently, but ESE can. 1) After quantization, the weight (12-bit) and index (4-bit) are not byte-aligned, and thus ESE groups both into 2 bytes. 2) ESE uses load balance-aware pruning to overcome the load imbalance that is caused by sparsity and reduce the hardware efficiency. 3) ESE takes advantage of the parallelism both inter sparse SpMV operation and intra SpMV operation.

Methodology

Processing units (PEs) of ESE are similar to those of EIE (prior work). Since a single element in the voice vector (input vector) is consumed by multiple PEs, operations of all the PEs have to be synchronized. To handle the element-wise multiplication, ElemMul units are outside the PEs.

Differences from prior work

Prior GRU/LSTM accelerators have only targeted parallelism for operations and not considered exploiting the sparsity. The first author’s previous work, EIE, is designed for sparse matrix multiplication, but ESE in this paper targets LSTM. EIE uses codebook based quantization, but ESE uses direct quantization.

Pros & cons

[Pros] Besides the benefits of sparse compression, ESE overcomes the load imbalance between PEs by taking load balance-aware pruning. ESE can work directly on the sparse model without interruption of irregular computation. ESE also supports processing multiple speech data concurrently. [Cons] However, there is a lack of explanation on how to deal with the load imbalance. Also, ESE is based on EIE, which is the author’s previous accelerator, and just adds element-wise functional units.

dac20

9. Scalable Multi-FPGA Acceleration for Large RNNs with Full Parallelism Levels [DAC’20]

Motivation

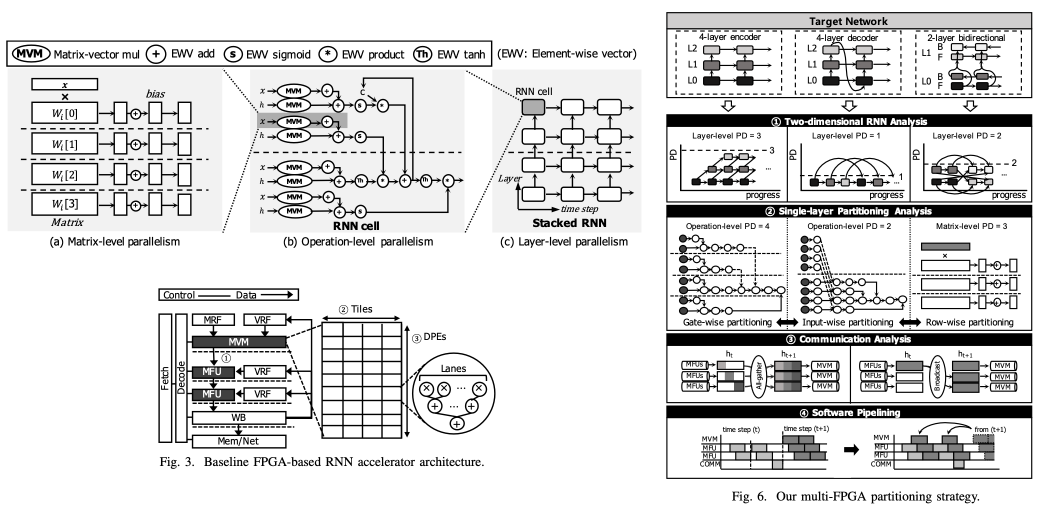

Large RNNs have the potential to be handled in parallel. Left figure (Fig.2 in paper) shows parallelism levels of large-scale and stacked RNNs from fine-grained (left) to coarse-grained (right) operations. At each parallelism level, the parallelism degrees are defined by RNN models and continue to grow as models become larger and stacked for more high-quality services. However, existing model parallelism methods suffer from severe HW underutilization when they distribute RNNs to multiple accelerators and thus fail to obtain the scalable performance. Therefore, this work introduces full parallelism levels of modern RNNs and proposes a systematic strategy to obtain optimal parallelism degrees at each level.

Methodology

This work introduces three parallelism levels of modern RNNs and proposes systematic strategies to obtain optimal parallelism degrees at each level. Fig. 6 summarizes four key ideas to find an optimal partitioning result for multiple FPGAs by exploiting the full parallelism of large-scale RNNs. 1) To find dependencies between input sequences and layers, two-dimensional RNN analysis is leveraged. Due to the analysis, the optimal number of FPGAs dedicated to each layer is determined natually. 2) To explore both operation-level (i.e., input/gate-wise) and matrix-level row-wise partitioning, which cannot be explored by conventional approaches at the same time, single- layer partitioning analysis is performed. This partitioning method provides optimal distributions that significantly reduce the load imbalance and vector reduction overheads. 3) To derive more detailed communication cost of RNN partitioning, communication analysis is considered. Lastly, 4) Software pipelining is applied to increase the utilization of FPGAs.

Pros & cons

[Pros] Based on this work, we can utilize full parallelism levels of modern RNN workloads and examine the performance impact of collective communications and software pipelining. Since this paper is well organized and contributions are notable, there is no particular weakness.

mnnfast

10. MnnFast: A Fast and Scalable System Architecture for Memory-Augmented Neural Networks [ISCA’19]

Motivation

Memory-augmented neural networks (MemNNs), which can make an inference with the previous history stored in memory, are known for their huge reasoning power and capability to learn from a large number of inputs rather than other networks. As the size of input datasets rapidly grows, the necessity of large-scale memory networks continuously arises. Although such large-scale memory networks provide excellent reasoning power, the current computer infrastructure cannot achieve scalable performance due to its limited system architecture.

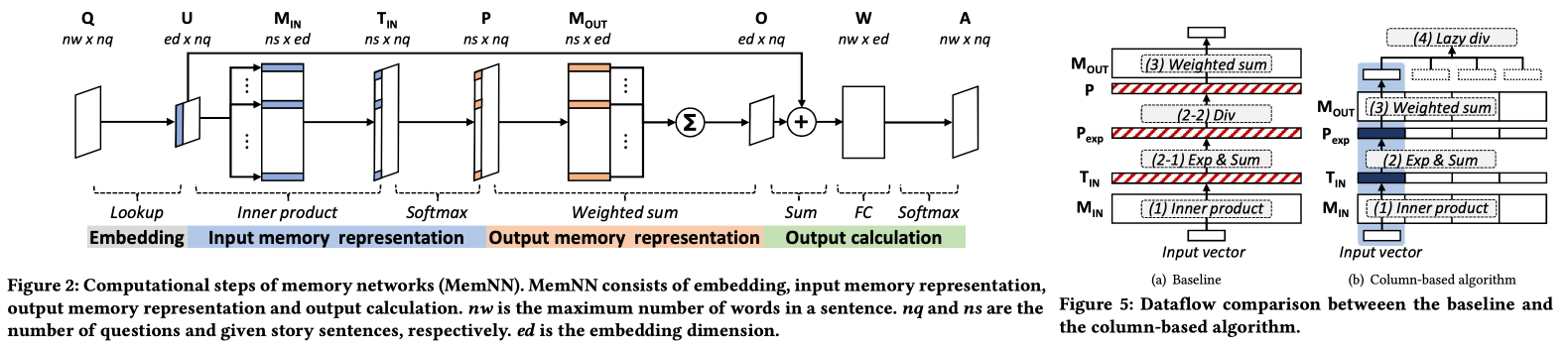

Methodology

MemNN has three performance problems: 1) high memory bandwidth consumption, 2) heavy computation, and 3) cache contention. During the embedding operation, MemNN looks up the embedding matrix to convert input sentences into internal state vectors. 1) Although a larger embedding dimension is beneficial for solving complicated questions, a higher memory bandwidth is required. In Figure 5, a baseline algorithm needs all temporary values of intermediate vectors. However, MnnFast overcomes this thorough column-based algorithm which enables MemNN to partially calculate output vectors. 2) To handle the significant computational overhead, a zero-skipping technique is used. 3) The large-scale MemNN suffers from huge cache contention between the embedding and inference operations. This cache contention dramatically increases the number of cache misses for the inference operation, which results in huge performance degradation. To overcome these limitations, they propose an embedding cache that is a dedicated cache for storing internal state vectors during the embedding operation.

Pros & cons

[Pros] This work points out the problem of MemNN operations well, and the three solutions are reasonable. [Cons] However, the third solution, embedding cache, can be only applied to custom hardware (FPGA). Thus, in terms of general purpose machines, only two solutions except for the third one are employed.

manna

11. Manna: An Accelerator for Memory-Augmented Neural Networks [MICRO’19]

Motivation

Memory-augmented neural networks (MANNs) can achieve one-shot learning and complex cognitive capabilities that are well beyond those of classical DNNs. For soft reads and writes to the differentiable memory, access to all the memory locations is required for each operation. Thus, the enhanced capabilities of MANNs (or the larger memories of MANNs) lead to a high computational cost, and results in poor performance of MANNs on modern CPUs, GPUs, and other accelerators. To address this, this paper presents Manna, a specialized hardware inference accelerator for MANNs.

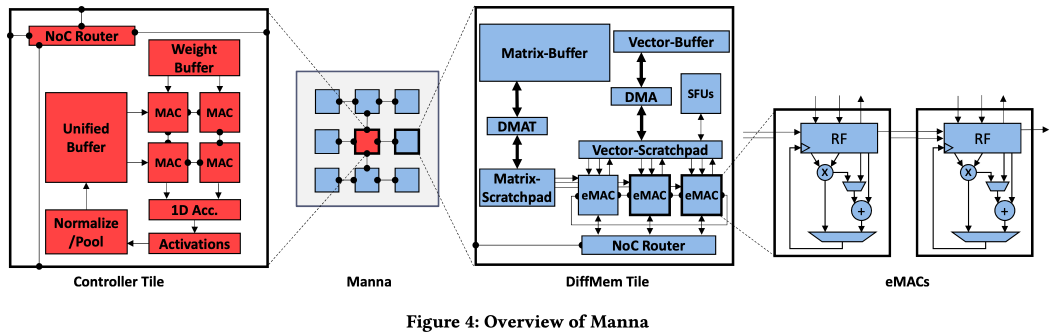

Methodology

Manna is a memory-centric, highly parallel CMOS-based architecture designed explicitly for memory-augmented neural networks. Google DeepMind’s neural turing machine (NTM) consists of a DNN controller (i.e., DNN network) and external differentable memory. Manna processes the DNN controller part with controller tile in Figure 4. Soft reads and writes to the differentiable memory are handled by remaining tiles called DiffMem tiles. A DiffMem tile has eMACs that can calculate MAC, and element-wise operations. They provide a compiler to map MANNs to Manna that minimize data movement.

Differences from prior work

Unlike Manna, prior works, such as MnnFast, are fixed-function architectures that are specialized for a specific class of MANNs, end-to-end memory networks (MemNets). However, Manna has sufficient programmability to realize a broad class of MANNs (e.g., NTMs and DNCs from Google Deepmind), which is important given the evolving nature of MANNs.

Pros & cons

[Pros] This work provides a detailed investigation of the computational characteristics of MANNs, and proposes an end-to-end, CMOS-based accelerator that is able to efficiently perform all kernels used in MANNs. [Cons] There are still opportunities to take advantage of the parallelism of MANNs.